Expulsion of Germans after World War II

|

|---|

| Flight and expulsion of Germans during and after World War II |

| (demographic estimates) |

| Background |

| German exodus from Eastern Europe Nazi-Soviet population transfers Potsdam Agreement |

| Wartime flight and evacuation |

| German evacuation East Prussia |

| Post-war flight and expulsion |

| Czechoslovakia Poland (incl. former German territories) Netherlands Romania |

| Later emigration |

| Emigration from Poland |

The later stages of World War II, and the period after the end of that war, saw the flight and forced migration of millions of German nationals (Reichsdeutsche) and ethnic Germans (Volksdeutsche) from various European states and territories, mostly into the areas which would become post-war Germany and post-war Austria. These areas included pre-war German provinces which were transferred to Poland and the Soviet Union after the war, as well as areas which Nazi Germany had annexed or occupied in pre-war Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, northern Yugoslavia and other states of Central and Eastern Europe.

The movement of Germans involved a total of at least 12 million people, with some sources putting the figure at 14 million, and was the largest movement or transfer of any single ethnic population in modern history. The largest numbers came from the former eastern territories of Germany acquired by Poland and the Soviet Union (about 7 million) and from Czechoslovakia (about 3 million). It was also the largest among all the post-war expulsions in Central and Eastern Europe, which displaced more than twenty million people in total. The events have been variously described as population transfer, ethnic cleansing or democide.

Many deaths were attributable to the flight and expulsions, with estimates ranging from 500,000 to 2 million, where the higher figures include deaths from famine and disease as well as from violent acts. Many German civilians were also sent to internment and labor camps.

The policy was part of the geopolitical and ethnic reconfiguration of postwar Europe; in part spoils of war, in part political changes in Europe following the war and in part retribution for atrocities and ethnic cleansings that had occurred during the war.

The displacements occurred in three somewhat overlapping phases, the first of which was the spontaneous flight and evacuation of Germans in the face of the advancing Red Army from mid-1944 to 1945, the second a disorganized expulsion of Germans immediately following the German defeat, and the third a more organized expulsion following the Potsdam Agreement, which redrew national borders and approved "orderly" and "humane" expulsions of Germans from Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary. The major expulsions were complete by 1950, when the total number of ethnic Germans still living in Eastern Europe was approximately 2.6 million, about 12% of the pre-war total.

Background

Before World War II, East-Central Europe generally lacked clearly shaped ethnic settlement areas. Rather, outside of some ethnic majority areas, there were vast mixed areas and abundant smaller pockets settled by various ethnicities. Within these areas of diversity, including the major cities of Central and Eastern Europe, regular interaction between various ethnic groups had taken place on a daily basis for as long as centuries, while not always harmoniously, on every civic and economic level.[1]

With the rise of nationalism in the 19th century, the ethnicity of citizens became an issue[1] in territorial claims, the self-perception/identity of states, and claims of ethnic superiority. The German Empire introduced the idea of ethnicity-based settlement in an attempt to ensure its territorial integrity, and was also the first modern European state to propose ethnic cleansing as a means of solving "nationality conflicts", intending the removal of Poles and Jews from the projected post-World War I "Polish Border Strip" and its resettlement with Germans.[2]

The Treaty of Versailles resulted in the creation or recreation of multiple nation-states across Central and Eastern Europe. Before World War I, these had been incorporated in the Austrian, Russian and German empires. Although the latter two arose and were named on the basis of their respective ethnic majorities, none of them were ethnically homogeneous. Attempts to change ethnic demographics were made, for example, in the newly recreated Polish state by reducing the number of Germans in the Polish Corridor.

During the German occupation of Eastern Europe under Nazism, many citizens of German descent registered with the Deutsche Volksliste. Some held important positions in the hierarchy of the Nazi administration and many participated in Nazi atrocities, causing resentment towards the Germans in general, which would later be used by the Allied politicians as one of the justifications for their expulsion.[3]

Internment and expulsion of Germans occurred during the war in both the United Kingdom and the United States. In the US internment program a total of 11,507 people of German ancestry were interned during the war, constituting 36.1% of the total internments in the Department of Justice's Enemy Alien Control Program.[4] Also 4,058 Germans were expelled from several Latin American countries to US internment camps.[5] Mass expulsion from the East and West coasts for reasons of military security were considered by the War Department, but not executed.[6]

The displacements discussed in this article occurred in three somewhat overlapping phases, the first of which was the spontaneous flight and evacuation of Germans in the face of the advancing Red Army, from mid-1944 to early 1945.[7] The second phase was the disorganized expulsion of Germans immediately following the Wehrmacht's defeat.[7] The third phase was a more organized expulsion following the Allied leaders' Potsdam Agreement,[7] which redefined the Central European administrative borders and legitimized "orderly" and "humane" expulsions of Germans from Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary.[8] Many German civilians were also sent to internment and labor camps.[9] The major expulsions were complete in 1950.[7]

The expulsions policy was part of the geopolitical and ethnic reconfiguration of postwar Europe, and in part retribution for Nazi Germany's initiation of the war and subsequent atrocities and ethnic cleansings in Nazi-occupied Europe.[10][11] The Allied leaders of the US, UK and the USSR had agreed in general before the end of the war that Poland's territory would be shifted west and the remaining German population expelled, and assured the leaders of the emigre governments of Poland and Czechoslovakia, both occupied by Nazi Germany, accordingly.[12][13][14][15]

Movements in the later stages of the war

Evacuation and flight to areas within Nazi Germany

,_ermordete_Deutsche.jpg)

Late in the war, as the Red Army advanced westward, many Germans were apprehensive regarding the impending Soviet occupation.[16][17] Most were aware of the Soviet reprisals against German civilians.[17] Soviet soldiers committed numerous rapes and other crimes.[16][17][18] News of atrocities like the Nemmersdorf massacre[16][17] was in part exaggerated and widely spread by the Nazi propaganda machine.

Plans to evacuate the ethnic German population westwards into Germany proper, from Eastern Europe and the eastern territories of Germany, were prepared by various Nazi authorities towards the end of the war. In most cases, however, implementation was delayed until Soviet and Allied forces had defeated the German forces and advanced into the areas to be evacuated. The responsibility for leaving millions of ethnic Germans in these vulnerable areas until combat conditions overwhelmed them can be attributed directly to the measures taken by the Nazis against anyone even suspected of 'defeatist' attitudes (as evacuation was considered) and the fanaticism of many Nazi functionaries in their execution of Hitler's 'no retreat' orders.[16][18][19]

The first mass exodus of German civilians from the eastern territories was composed of both spontaneous flight and organised evacuation, starting in the summer of 1944 and continuing through the early spring of 1945.[7] Conditions turned chaotic during the winter, when miles-long queues of refugees pushed their carts through the snow trying to stay ahead of the advancing Red Army.[17][20]

Between 6[21] and 8.35[22] million Germans fled or were evacuated from the areas east of the Oder-Neisse line before the Soviet Army took control of the region.[21] Refugee treks which came within reach of the advancing Soviets suffered high casualties when targeted by low-flying aircraft, and some were rolled over by tanks.[17] Many refugees tried to return home when the fighting ended. Before June 1, 1945, some 400,000 crossed back over the Oder and Neisse rivers eastward, before Soviet and Polish communist authorities closed the river crossings; another 800,000 entered Silesia from Czechoslovakia.[23]

Evacuation and flight to Denmark

From the Baltic coast, many soldiers and civilians were evacuated by ship in the course of Operation Hannibal.[17][20] Between January 23, 1945 and May 5, 1945, up to 250,000 Germans primarily from East Prussia, Pomerania, and the Baltic states were evacuated to Nazi-occupied Denmark,[24][25] based on an order issued by Hitler on February 4, 1945.[26] Thus, when the war ended, the German refugee population in Denmark amounted to 5% of the total Danish population. The evacuation focused on women, the elderly and children - a third were under the age of fifteen.[25]

After the war, they were interned in several hundreds of camps throughout Denmark, the largest of which was the Oksbøl Refugee Camp with 37,000 inmates.[25] The camps were guarded by Danish military units.[25]

The situation eased after 60 Danish clergy spoke up in defence of the refugees in an open letter,[27] and Social Democrat Johannes Kjærbøl took over the administration of the refugees on September 6, 1945.[28] On May 9, 1945, the Red Army occupied the island of Bornholm; between May 9 and June 1, 1945 the Soviets shipped some 3,000 refugees and 17,000 Wehrmacht soldiers from there to Kolberg.[29]

In 1945, 13,492 German refugees died, among them some 7,000 children[25] under five years of age.[30] According to Danish physician and historian Kirsten Lylloff, these deaths were partially due to denial of medical care by Danish medical staff, both the Danish Association of Doctors and the Danish Red Cross refusing medical treatment of the refugees starting in March 1945.[25]

The last refugees left Denmark on 15 February 1949.[31] In the Treaty of London, signed February 26, 1953, West Germany and Denmark agreed on compensation payments of 160 million Danish Crowns, which West Germany paid between 1953 and 1958.[32]

Expulsions following Nazi Germany's defeat

The Second World War ended in Europe with Nazi Germany's defeat in May 1945. By this time, all of Eastern and much of Central Europe was under Soviet occupation. This included most of the historical German settlement areas, as well as the Soviet occupation zone in eastern Germany. The Allies settled on the terms of occupation, the territorial truncation of Germany, and the expulsion of ethnic Germans from post-war Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary to the Allied Occupation Zones in the Potsdam Agreement,[33][34] drafted during the Potsdam Conference between 17 July and 2 August 1945. Article XII of the agreement is concerned with the expulsions and reads:

The Three Governments, having considered the question in all its aspects, recognize that the transfer to Germany of German populations, or elements thereof, remaining in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, will have to be undertaken. They agree that any transfers that take place should be effected in an orderly and humane manner.[35]

The agreement further called for equal distribution of the transferred Germans between American, British, French and Soviet occupation zones comprising post-World War II Germany.[36]

Expulsions that took place before the Allies agreed on the actual terms at Potsdam are referred to as "wild" expulsions (German: Wilde Vertreibungen). They were conducted by military and civilian authorities in Soviet-occupied post-war Poland and Czechoslovakia during the spring and summer of 1945.[34][37] The Potsdam Declaration requested that those countries temporarily stop expulsions due to the refugee problems created by the expulsion of Germans before the Potsdam meeting.[34] While expulsions from Czechoslovakia were temporarily slowed down, this was not true for Poland and the former eastern territories of Germany.[36] Sir Geoffrey Harrison, one of the drafters of the cited Potsdam article, stated that the "purpose of this article was not to encourage or legalize the expulsions, but rather to provide a basis for approaching the expelling states and requesting them to co-ordinate transfers with the Occupying Powers in Germany."[38]

After Potsdam, a series of expulsions of ethnic Germans occurred throughout the Soviet-controlled Eastern European countries.[39][40] Property and materiel in the affected territory that had belonged to Germany or to Germans was confiscated and either transferred to the Soviet Union, nationalised, or redistributed among the citizens. Of the many post-war forced migrations, the largest was the expulsion of ethnic Germans from Central and Eastern Europe, primarily from the territory of 1937 Czechoslovakia (which included the historically German-speaking area in the Sudeten mountains along the German-Czech-Polish border (Sudetenland)), and the territory that became post-war Poland. Poland's post-war borders were shifted west to the Oder-Neisse line, deep into former German territory.[34]

Expulsions and resettlements of other ethnicities took place contemporaneously with the expulsion of the Germans. Both ethnic Germans and most of the Italians were expelled from Tito's Yugoslavia.[41] As well as the ethnic Germans, Poland also expelled 482,000 of the 622,000 ethnic Ukrainians living in Poland, resettling the remaining 140,000 during Operation Vistula.[40] In Czechoslovakia, not only were Sudeten Germans expelled, but also the Hungarian minority in Slovakia[40] during the ocysta. Post-war Lithuania and Ukraine expelled both the German minority and the Poles.[40] The same happened to the remaining Polish population in Belarus.

Czechoslovakia

- See also: History of Czechoslovakia, Beneš decrees, Sudetenland, Ústí massacre, Brno death march

Before the 1938 German annexation of the Sudetenland, more than 22.3% of the population in Czechoslovakia had been of German ethnicity.[42] In May 1945, about 3,050,000 Germans remained in the Sudetenland and other Czechoslovak territories.[43][44]

During the German occupation of Czechoslovakia, especially after the Nazi reprisals for the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich, most of the Czech resistance groups demanded that the "German problem" be solved by transfer/expulsion. These demands were adopted by the Government-in-Exile, which sought the support of the Allies for this proposal, beginning in 1943.[45] The final agreement for the transfer of the Germans was not reached until the Potsdam Conference.

It is estimated that between 700,000 and 800,000 Germans were affected by "wild" expulsions between May and August 1945.[43] The expulsions were encouraged by Czechoslovak politicians and were generally executed by the order of local authorities, mostly by groups of armed volunteers and the army.[47] Secret service officer Bedřich Pokorný participated in several crimes.[48]

Transfer according to the Potsdam agreements proceeded from January to October 1946. 1.9 million ethnic Germans were expelled to the American zone of what would become West Germany. More than 1 million were expelled to the Soviet zone which later became East Germany.[49] About 250,000 ethnic German anti-fascists and ethnic Germans crucial for industry were allowed to remain in Czechoslovakia.[50] Male Germans with Czech wives were expelled, often with their spouses, while ethnic German women with Czech husbands were allowed to stay.[51] Still, many people with German surnames were counted as "Czechs" and allowed to stay, leading to odd situations such as the current president and prime minister of the Czech Republic and the second president of Slovakia having German surnames.

Estimates of casualties range from 10,000 to 250,000 people.[52] In 1995, based on newly available data, a German-Czech commission revised previous estimates of 250,000 deaths down to between 15,000 and 30,000.[53] These include murders, suicides, starvations, illness, deaths in internment camps,[52] and deaths from natural causes.[54]

Numbers of skilled Sudeten Germans were forced to remain.[55]

Hungary

In contrast to the expulsions from other states, the expulsion of the Germans from Hungary was dictated from outside the nation,[56] and began on 22 December 1944 when the Soviet Commander-in-Chief ordered the expulsions. Three percent of the German pre-war population (about 20,000 people) had been evacuated by the Volksbund before that. They went to Austria, but many of them returned home in the spring. Overall, some 60,000 ethnic Germans had fled.[39] In January 1945, 32,000 ethnic Germans were arrested and transported to the Soviet Union as forced laborers. In some villages, the entire adult population were taken to labor camps in the Donets Basin.[39] Many died there as a result of hardships and ill-treatment. Overall, between 100,000 and 170,000 Hungarian ethnic Germans were transported to the Soviet Union.[57]

In 1945, official Hungarian figures showed 477,000 German speakers in Hungary, 303,000 of whom had declared German nationality.[57] Of the German nationals, 33% were children younger than 12 or elderly people over 60; another 51% were women.[57]

On 29 December 1945, the communist Hungarian Government ordered the expulsion of everyone who had declared himself a German in the 1941 census, or had been a member of the Volksbund, the SS, or any other armed German organisation. Accordingly, mass expulsions began.[39] The rural population was affected more than the urban population or those ethnic Germans with needed skills, such as miners.[58][59] Germans married to Hungarians were not expelled, regardless of sex.[51] The first 5,788 expellees left from Budaörs (Wudersch) on January 19, 1946.[58] About 180,000 German-speaking Hungarian citizens were deprived of their citizenship and all possessions, and expelled to the Western zones of Germany.[60] Up to July 1948, a further 35,000 people were expelled to the Eastern zone of Germany.[60] Most of the expellees found new homes in the Southwest German province of Baden-Württemberg,[61] but many also in Bavaria and Hesse. Other research indicates that, between 1945 and 1950, 150,000 were expelled to western Germany, 103,000 to Austria, and none to eastern Germany.[50] During the expulsions, numerous organized protest demonstrations by the Hungarian population took place.[62]

Acquisition of land for distribution to Hungarian refugees and nationals was one of the main reasons for the expulsion of the ethnic Germans from Hungary,[59] and the botched organisation of the redistribution led to social tensions.[59]

By the end of the expulsions, an estimated 200,000 Germans remained in Hungary,[39] (Overy states 270,000[50]), but only 22,445 declared themselves German in the 1949 census.[59] An order of 15 June 1948 halted the expulsions, and a governmental decree of 25 March 1950 declared all expulsion orders void, allowing the expellees to return if they so wished.[59] After the fall of Communism, German victims of expulsion and Soviet forced labour were rehabilitated.[61] Post-Communist laws allowed expellees to be compensated, to return and to buy property.[63] There are no tensions in Hungarian-German relations regarding the expellee issue.[63]

The Netherlands

After World War II, the Dutch government decided to expel the 25,000 Germans living in the Netherlands.[64] The Germans, even though they often had Dutch spouses and children, were called 'hostile subjects' (Dutch: vijandelijke onderdanen).[64] The operation began on 10 September 1946 in Amsterdam, when ethnic Germans and their families were arrested at their homes in the middle of the night and given one hour to pack 50 kg of luggage. They were allowed to take just 100 Guilders with them. The remainder of their possessions were seized by the state. They were taken to internment camps near the German border, the largest of which was Mariënbosch near Nijmegen. In all, about 3,691 Germans (less than 15 percent of the 25,000 total number of Germans in the Netherlands) were expelled.

The Allied forces occupying the Western zone of Germany opposed this operation, fearing that other nations might follow suit. The Western zone was not in an economic condition to receive large numbers of expellees at that time. British troops retaliated by evicting 100,000 ethnic Dutch citizens in Germany to the Netherlands.

The operation ceased in 1948. On 26 July 1951, the state of war between the Netherlands and Germany officially ended, and the ethnic Germans were no longer regarded as state enemies.

Poland, including former German territories

Throughout 1944 and into the first months of 1945, as the Red Army advanced through Eastern Europe and the provinces of eastern Germany, some Soviet and Allied troops and sometimes civilian populations exacted revenge on ethnic Germans and German nationals. While many had already fled ahead of the advancing Soviet Army, frightened by rumors of Soviet atrocities which in some cases were exaggerated and exploited by Nazi Germany's propaganda,[65] millions still remained, and an additional million returned as soon as military operations in their homeland ceased.[66] The Polish courier Jan Karski warned US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1943 of the possibility of Polish reprisals, describing them as "unavoidable" and "an encouragement for all the Germans in Poland to go west, to Germany proper, where they belong" (Karski's 1943 reference to "Poland" meant the pre-war aka 1937 bordered area of Poland).[67] Almost the complete male German population remaining east of the Oder and Neisse, numbering several tens of thousands, were arrested as "Hitlerists" by the Soviet secret police, NKVD.[66] Only a minority were Nazi party members.[66]

In 1945, the eastern territories of Germany (most of Silesia and Pomerania, East Brandenburg, and East-Prussia), as well as Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany (especially Warthegau and Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia) were occupied by the Red Army and Soviet-controlled Polish military forces. Early expulsions were undertaken by the Polish communist military authorities[68] even before the Potsdam Conference placed them under temporary Polish administration pending the final Peace Treaty,[69] to ensure their later integration into an ethnically homogeneous Poland[70] as envisioned by the Polish communists: "We must expel all the Germans because countries are built on national lines and not on multinational ones".[71][72] Germans were defined as either Reichsdeutsche, people enlisted in first or second Volksliste groups, or those who held German citizenship. About 1.1 million[73] German citizens of Slavic ancestry were "verified" as "autochthonous" Poles.[74] Of these, most were not expelled; nevertheless hundreds of thousands chose to emigrate to Germany after 1950, including most of the Masurians of East Prussia.[75]

At the Potsdam Conference (17 July - 2 August 1945) the territory to the east of the Oder-Neisse line was assigned to Polish and Soviet Union administration pending the Final Peace Treaty. All Germans had their property confiscated and were placed under restrictive jurisdiction.[74][76] The Silesian voivode Aleksander Zawadzki in part expropriated the property of the German Silesians already on 26 January 1945, another decree of 2 March expropriated that of all Germans east of the Oder and Neisse, and a subsequent decree of 6 May declared all "abandoned" property as belonging to the Polish state.[77] Additionally, Germans were not permitted to own Polish currency, the only legal currency since July, other than earnings from work assigned to them.[78] The remaining population was de facto deprived of all civil rights, and faced theft and looting and also in some instances rape and murder by the Polish militia, in addition to similar acts by criminal gangs that were neither prevented nor prosecuted by the Polish militia and judiciary.[79]

Subsequently, most remaining Germans were expelled from pre-war Poland and the 'recovered territories' (formerly eastern Germany) to the territory west of the Oder-Neisse Line. Some, before their expulsion, were used as forced labor in communist-administered camps[39] such as those run by Salomon Morel and Czesław Gęborski. These included Central Labour Camp Jaworzno, Central Labour Camp Potulice, Łambinowice and Zgoda labour camp. Besides these large camps, numerous other forced labor, punitive and internment camps, urban ghettos and detention centres, sometimes consisting only of a small cellar, were set up.[76] Germans considered "indispensable" for the Polish economy were retained until the early 1950s,[76] though virtually all had left by 1960.[75] Close to 165,000 Germans were transported to the Soviet Union for forced labor, where most of them perished.[76] According to Reichling [80] 520 000 were transported, 185 000 of them died.

The attitude of the surviving Polish civilians, many of whom had experienced brutalities and atrocities only surpassed by the German policies against Jews of all nationalities during the Nazi occupation, combined with the fact that the Germans had recently expelled more than a million Poles from territories they annexed during the war, was ambiguous.[17] Some engaged in looting and various crimes, including murders, beatings and rapes, against Germans.[17] On the other hand, in many instances Poles, including some who had been made slave labourers by the Germans during the war, protected Germans, for instance by disguising them as Poles.[17] Moreover, in the Opole (Oppeln) region of Upper Silesia, citizens who claimed Polish ethnicity were allowed to remain. In fact, some (though not all) had uncertain nationality or actually considered themselves to be Germans. Their status as a national minority was accepted in 1955, along with state subsidies, with regard to economic assistance and education.[81] The attitude of Soviet soldiers was also ambiguous. Many committed atrocities, most notably rape and murder,[18] and did not always distinguish between Poles and Germans, mistreating them equally.[82] Yet some other Soviets were taken aback by the brutal treatment of the German civilians and tried to protect them.[83]

Tomasz Kamusella cites estimates of 7 million expelled during both the "wild" and "legal" expulsions from the recovered territories from 1945 to 1948, plus an additional 700,000 from areas of pre-war Poland.[76] Overy cites approximate totals of those evacuated, migrated, or expelled between 1944 and 1950 as: from East Prussia - 1.4 million to West Germany, 609,000 to East Germany; from West Prussia - 230,000 to West Germany, 61,000 to East Germany; from the former German provinces east of the Oder-Neisse, encompassing most of Silesia, Pomerania and East Brandenburg - 3.2 million to West Germany, 2 million to East Germany.[84]

Romania

The flight of ethnic Germans from Romania began in the fall of 1944.[39] Early in 1945, Soviet occupation forces began the forced expulsion of ethnic Germans. 213,000 of Romania's ethnic Germans were eventually evacuated, expelled, or emigrated. As with all of the population migrations at this time, some lost their lives in the process. Of a pre-war ethnic German population of 786,000, about 400,000 resided in Romania in 1950. There were still 355,000 in 1977. During the 1980s many started to leave the country, with over 160,000 leaving in 1989 alone. By 2002, the number of ethnic Germans was 60,000 citizens.[39][50]

Soviet Union and annexed territories

The Baltic, Bessarabian and ethnic Germans in areas that became Soviet-controlled following the partition of eastern Europe by Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin in the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939 were resettled to the Third Reich, including annexed areas like Warthegau, during the Nazi-Soviet population exchange. Only a few returned when Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union and temporarily gained control of those areas. These returnees were employed by the Nazi occupation forces to establish a link between the Nazi administration and the local population. Those resettled elsewhere shared the fate of the other Germans in their resettlement area.[85]

After the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, Stalin (in September 1941) ordered the forced resettlement of ethnic Germans living in Soviet-controlled parts of the USSR, as a potentially hostile ethnic population - most notably about 400,000[86] Volga Germans and about 80,000[86] Germans from Leningrad (St. Petersburg) and other areas - to remote areas in Siberia, Kyrgystan, and Kazakhstan, where they were forced to remain after the war.[41][86] Many died during the resettlement.[86] The able-bodied men and childless women were enlisted in the trud army ("working army") for forced labour.[86]

Those ethnic Germans who remained in Soviet-controlled territory despite the Nazi-Soviet population transfers, and whose settlement areas had become German-controlled before the Soviet authorities could resettle them, remained where they were until 1943, when the Red Army liberated Soviet territory and the Wehrmacht withdrew westward.[86] From January 1943, most of these ethnic Germans moved in treks to the Warthegau or to Silesia, where they were to settle.[87] Between 250,000 and 320,000 had reached Nazi Germany by the end of 1944.[88] On their arrival, they were placed in camps and underwent 'racial evaluation' by the Nazi authorities, who dispersed those deemed 'racially valuable' as farm workers in the annexed provinces, while those deemed to be of "questionable racial value" were sent to work in the Altreich.[89] The Red Army captured these areas in early 1945, and 200,000 Soviet Germans had not yet been evacuated by the Nazi authorities,[87] who were still occupied with their 'racial evaluation'.[90] They were regarded by the USSR as Soviet citizens and repatriated to camps and special settlements in the Soviet Union.[87] Some 70,000 to 80,000 who found themselves in the Soviet occupation zone after the war were treated the same way, based on an agreement with the Western Allies.[87] The death toll during their capture and transportation was estimated at 15% to 30%, and many families were torn apart.[87] The special "German settlements" in the post-war Soviet Union were controlled by the Internal Affairs Commissioner, and the inhabitants had to perform forced labour until the end of 1955.[87] At this time, all of the 1.5 million ethnic Germans in the Soviet Union were in custody.[87] They were released after Stalin's death by an amnesty decree of 13 September 1955[87] and the Nazi collaboration charge was revoked by a decree of 23 August 1964,[91] yet no individual's former property was restored.[87][91]

Different situations emerged in northern East Prussia regarding Königsberg (renamed Kaliningrad) and the adjacent Memel territory around Memel (Klaipėda). The Königsberg area of East Prussia was annexed by the Soviet Union, becoming an exclave of the Russian Soviet Republic. Memel was integrated into the Lithuanian Soviet Republic. Many Germans were evacuated from East Prussia and the Memel territory by Nazi authorities during Operation Hannibal or fled in panic as the Red Army approached. At the war's end, most surviving Germans were soon expelled.[39] Ethnic Russians and the families of military staff were settled in the area. In June 1946, 114,070 Germans and 41,029 Soviet citizens were registered as living in the Kaliningrad Oblast, with an unknown number of unregistered Germans ignored. However, between June 1945 and 1947, roughly half a million Germans were expelled.[92] Between 24 August and 26 October 1948, 21 transports with a total of 42,094 Germans left the Kaliningrad Oblast for the Soviet Occupation Zone. The last remaining Germans were expelled between November 1949[39] (1,401 persons) and January 1950 (7 persons).[93] Thousands of German children, called the wolf children, had been left orphaned and unattended or died with their parents during the harsh winter without food. Between 1945 and 1947, some 600,000 Soviet citizens settled the oblast.[94]

Yugoslavia

After World War II, the majority of the roughly 500,000 German-speaking people in Yugoslavia (mostly Danube Swabians) left for Austria and West Germany.[39] After 1950, thanks to the "displaced persons" act (of 1948), they were also able to emigrate to the USA. Because of the support of some ethnic Germans for Nazi Germany, for instance, enlistment in the 7th SS Volunteer Mountain Division Prinz Eugen, all ethnic Germans suffered persecution and sustained great personal and economic losses.[39] Many were killed as local populations and partisans took revenge for Nazi atrocities,[39][95] in mass rapes and detention in concentration camps.[95] At least 5,800 were shot;[96] those surviving were compelled to forced labour.[96]

In late 1944 the Soviets transported 27,000 to 30,000 ethnic Germans, 90% of them women, to the Donets basin for forced labour; 16% perished.[39][96]

In Slovenia, the German population at the end of World War II was concentrated in Slovenian Styria, more precisely in Maribor, Celje, and a few other smaller towns (like Ptuj and Dravograd), and in the rural area around Apače on the Austrian border. The second largest ethnic German community in Slovenia was the predominantly rural Gottschee County around Kočevje in Lower Carniola, south of Ljubljana. Smaller numbers of ethnic Germans also lived in Ljubljana and in some western villages in the Prekmurje region. In 1931, the total number of ethnic Germans in Slovenia was around 28,000: around half of them lived in Styria and in Prekmurje, while the other half lived in the Gottechee County and in Ljubljana. In April 1941, southern Slovenia was occupied by Italian troops. By the spring 1942, the ethnic Germans from Gottschee/Kočevje were transferred to German-occupied Styria. Most of them were resettled to the Posavje region (a territory along the Sava river between the towns of Brežice and Litija), from where around 50,000 Slovenes had been expelled. As German forces retreated before the Yugoslav Partisans, most ethnic Germans fled with them in fear of reprisals. By May 1945, only few Germans remained, mostly in the Styrian towns of Maribor and Celje. The Liberation Front of the Slovenian People expelled most of the remainder after it seized complete control in the region in May 1945.[96] Many were imprisoned in the concentration camps of Šterntal and Teharje.

The government nationalized their property on a "decision on the transition of enemy property into state ownership, on state administration over the property of absent persons, and on sequestration of property forcibly appropriated by occupation authorities" of 21 November 1944 by the Presidency of the Anti-Fascist Council for the People's Liberation of Yugoslavia[96][97]

After March 1945, ethnic Germans were placed in so-called 'village camps'.[98] Separate camps existed for those able to work and for those who were not.[98] In the latter camps, containing mainly children and the elderly, the mortality rate was about 50%.[99] Most of the children under 14 were then placed in state-run homes, where conditions were better, though the German language was banned.[99] These children were later given to Yugoslav families, and not all German parents seeking to reclaim their children in the 1950s were successful.[99]

The camp system was shut down in March, 1948.[99] A total of 48,447 people had died in the camps; 7,199 were shot by partisans, and another 1,994 were taken to Soviet camps.[100] Those Germans still considered Yugoslav citizens were employed in industry or the military, but could buy themselves free of Yugoslav citizenship for the equivalent of three months' salary.[99] By 1950, 150,000 of these had made their way to post-war Germany, another 150,000 to Austria, 10,000 to the USA, and 3,000 to France.[99]

82,000 ethnic Germans remained in Yugoslavia in 1950.[50]

Kehl

The population of the Southwest German town of Kehl, on the right bank of the Rhine right bank opposite Strasbourg, fled and were evacuated in the course of the Battle of France, on 23 November 1944.[101] French forces occupied the town in March 1945 and prevented the inhabitants from returning until 1953.[101]

Demography

Expulsion area

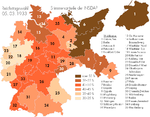

During the period of 1944/1945 - 1950, possibly as many as 14 million[102][103] Germans fled, were evacuated, or were expelled as a result of actions of Nazi Germany, the Red Army, civilian militias, and/or the organized efforts of governments of the reconstituted states of Eastern Europe. Rudolph Joseph Rummel summarised different estimates in a range between 11.6 and 18 million, and concluded that most probably 15 million people were affected.[104] Between 1944 and 1948, at least 12 million had been expelled and resettled to post-war Germany, most of them (11.5 million) from the territories of post-war Poland and Czechoslovakia.[105] These figures include neither those expelled to Austria nor those who took their post-war residence elsewhere.[105] About three million Germans remained in the expulsion areas, but gradually emigrated westward in the Cold War era and thereafter.[106]

The areas from which the Germans fled or were expelled were subsequently repopulated by nationals of the states to which that territory now belonged, many of whom were themselves expellees from lands further east.

Post-war Germany and Austria

On 29 October 1946, the Allied Occupation Zones in Germany already held 9.5 million refugees and expellees: 3.6 million in the British zone, 3.1 million in the U.S. zone, 2.7 million in the Soviet zone, 100,000 in Berlin and 60,000 in the French zone.[107]

These numbers subsequently increased, with two million additional expellees counted in West Germany in 1950 for a total of 7.9 million[108] (16.3% of the population).[107][109] By origin, the West German expellee population consisted of about 5.5 million people from post-war Poland, primarily the former German East/new Polish West, two million from former Sudetenland, and the rest primarily from Southeast Europe, the Baltic states and Russia.[106]

In the Soviet zone the number rose to 4.2 million by 1948 (24.2% of the population) and 4.4 million[108] by 1950,[109][110] when the Soviet zone had become the state of East Germany.

Thus, a total of 12.3 million Heimatvertriebene comprised 18% of the population in the two German states created from the Allied occupation zones (Federal Republic of Germany and German Democratic Republic) in 1950, while another 500,000 expellees found refuge in Austria and other countries.[109] Because of their influx, the population of the post-war German territory had risen by 9.3 million (16%) from 1939 to 1950 despite wartime population losses.[108]

After the war, the area west of the new eastern border of Germany was crowded with expellees, some of them living in camps, some looking for relatives, some just stranded. Between 16.5%[111] and 19.3%[102] of the total population were expellees in the Western occupation zones and 24.2% in the Soviet occupation zone.[111] Expellees made up 45% of the population in Schleswig-Holstein, 40% in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern; similar percentages existed along the eastern border all the way to Bavaria, while in the westernmost German regions the numbers were significantly lower, especially in the French zone of occupation. Of the expellees initially stranded in East Germany, many migrated to West Germany, making up a disproportionally high number of post-war inner-German East-West migrants (close to one million of a three million total between 1949, when the West and East German states were created, and 1961, when the inner-German border was closed).[112]

Casualties

Estimates of total deaths of German civilians have ranged from 500,000[113].[114] to a maximum of 3.2 million people. Although the German government's official estimate of deaths due to the expulsions stood at 2.2 million for several decades, recent analysis has led some historians to the conclusion that the actual number of deaths attributable to the expulsions was much lower - in the range of 500,000 to 1.1 million. The higher figures (up to 3.2 million) typically include all deaths related to the 1939-1945 war including those serving in the German Armed Forces. The number of deaths and their causes remain a topic of tense debate among historians.

Casualty estimates vary. Estimates were calculated by balancing pre- and post-expulsion populations and by counting verified deaths. There is a discourse regarding the validity of the methods and their results. Both the population balance figures, in the range of 2 to 3 million,[102][103][115][116][117] as well as the number of verified deaths in the range of 500,000 to 600,000, are cited in current discussions.[115][116]

Early estimates - population balances

One of the first attempts at estimating the number of deaths due to expulsions was published in 1953 by Bruno Gleitze,[118] who was trying to come up with an estimate of overall German civilian casualties during World War II. Because accurate data on individual deaths was not available, Gleitze had to resort to the a 'population balance method' which estimates the likely number of Germans in the relevant territories before the expulsions and compares it to the population that arrived in the West as expellees.[115][119] Gleitz estimated 800,000 deaths among "Eastern Germans" (the population that corresponded to the later terminology of "expellees") although he failed to take into account decreased wartime fertility (due to the fact that most young males were away at the front). According to the German historian Ingo Haar, because of this Gleitz overestimated the likely number of deaths for all of Germany by about 43%[118].

In 1952 a commission headed by Theodor Schieder was set up on behalf of the West German government.[120] Schieder was a former member of the Nazi party who in 1939 advocated "dejewification" of territories conquered by Nazi Germany in preparation for German colonisation.[121][122] The commission consisted of several historians,[123] including Werner Conze (who had also previously advocated "dejewification" of territory occupied by Nazi Germany)[121], Adolf Diestelkamp, Rudolf Laun, Peter Rassow and Hans Rothfels.[124] The commission also included then young historians of 'the second generation' like Martin Broszat and Hans-Ulrich Wehler.[125] In 1953, West German minister for expellees Hans Lukaschek presented an interim report of the commission for the Oder-Neisse territory, estimating 2.167 million deaths out of twelve million expellees, including 500,000 Wehrmacht and as many aerial warfare casualties.[120] Also in 1953, Gotthold Rhode estimated the casualties to be 3.14 million.[120] In 1958, the West German government commission issued its final report, estimating a total of some 2.225 million deaths.[116]

Demographer Rüdiger Overmans says these numbers do not represent confirmed deaths (see section below) but rather persons who could not be accounted for. According to Overmans, based on the documents used by the commission, it is only possible to establish the deaths of 500,000 individuals and there is nothing in German historiography which could explain the other 1.5 million supposed deaths.[53]

In 1998 Rudolph Joseph Rummel examined the data collected by numerous English-language authors and found a range from 528,000 to 3,724,000 deaths due to the expulsions. By taking the average of these sources, he calculated the total post-war deaths to be 1,863,000.[126] He estimated an additional one million civilians perished during the wartime flight and evacuation before the expulsions.[126]

Research tracing individual fates

Already in 1953, the West German government ordered that, in addition to the employment of demographic methods, data be collected about confirmed individual fates.[127] By 1965, the Suchdienst (search service) of the German church was able to confirm 470,000 deaths[116] and an additional 1,906,000 cases of persons missing. The Suchdienst study was based on own research and questionnaires issued to expellees by expellee organisations, the results of which were archived in the Heimatsortkartei, "homestead register".[127] After its completion, the German church numbers were archived and not released to the general public - according to Ingo Haar, this was due to a fear that they were "too low" and would lead to "politically undesirable conclusions".[118]

In 1969, the Federal West German government ordered a further study be conducted by the German Federal Archives,[128][129] which was finished in 1974[116][129] and published in 1989.[129] Thereby false positives from the Suchdienst report were excluded and additional sources evaluated, resulting in a number of 630,000 deaths, including 400,000 in the Oder-Neisse territory.[129] Besides confirmed deaths, this study also included people believed to be dead and excluded about 600,000 Soviet Volksdeutsche deported within the Soviet Union.[129] According to Haar, the study details its figures as follows: 120,000 deaths due to Red Army atrocities, between 40,000 and 100,000 deaths resulting from the conditions in Soviet and Polish camps, 200,000 deportees to the Soviet Union, 130,000 deaths in Czechoslovakia of which 6,000 were confirmed, and 80,000 deaths in Yugoslavia.[129] Overmans cites the study as follows: 260,000 killed by the Red Army and their allies in Eastern Europe, 160,000 deaths resulting from the conditions in deportation camps and in transit, 205,000 forced labourers in the Soviet Union; the other numbers are the same Haar cites.[130] The German Federal Archives study also rejected the earlier Schieder numbers and affirmed rough agreement with the estimates made by the German church. However, the findings of this new commission were kept secret for 15 years in order not to disturb West German-Polish rapprochment, and were only made public in 1989.[118]

According to the 1974 study by the German Archives cited by Overmans, 400,000 Germans died in postwar-boundary Poland. The study itself estimates 200,000 deaths as forced labourers in the USSR, 120,000 killed by the Soviets and their allies, and 100,000 deaths from postwar incarcerations and expulsions of remaining Germans on behalf of the Polish 'Provisional Government of National Unity'. [128]

In 1994, the organisation of German expellees from Yugoslavia revised the figures for Yugoslavia, giving a total of 68,664 verified deaths.[131] In 1995, a joint German and Czech commission of historians revised the number of civilian deaths in Sudetenland, from Schreider's previous estimate of 250,00 down to between 15,000 and 30,000 deaths (or by a factor of 10), based on Overmans' earlier work.[116]

Overmans and Haar cited these studies on confirmed deaths, saying they result in a number between 500,000 and 600,000.[53][129] Both believe that further research is needed to determine the fate of the estimated additional 1.5 million civilians listed as missing.[128] However, Overmans says that the 600,000 deaths found by the German Federal Archives are as close to the truth as can be established with present data.[53] Haar says that all reasonable estimates of deaths from expulsions lie between around 500,000 and 600,000.[118]

Discourse

Overmans studied overall casualties among Wehrmacht soldiers during the war and found that the previous estimates, especially in the final stages of the war, were about two million short of the actual death toll,[116] which was 5.3 million rather than the previously believed 2.938 million.[132] In his 2004 book, he showed that Wehrmacht deaths from the expulsion areas were about 1.444 million, and thus 334,000 higher than the 1.1 million figure the Schieder commission, lacking documents available today, had used to compute the figures of civilian deaths.[114] Overmans further pointed out that the 2.225 million number estimated by the commission would imply that the casualty rate among the expellees was equal to or higher than that of the Wehrmacht, which he found implausible.[53] In addition to his research about Wehrmacht deaths, Overmans said the difference between the 2.225 million missing persons and the some 500,000 deaths that so far could be verified includes people who never existed[116] or were never born (due to lower wartime fertility), German Jews who had been murdered by the German state, and individuals who were deported to the Soviet Union.[118] He also states that the 2.225 million number relies on improper statistical methodology and incomplete data, particularly in regard to the expellees who arrived in East Germany.[118] Haar questions the validity of population balances in general.[133]

Christoph Bergner, former Secretary of State in Germany's Bureau for Internal Affairs, outlined the stance of the respective governmental institutions on German radio on 29 November 2006.[134] Bergner said that the numbers are not contradictory, and that the lower 400,000 to 600,000 estimates of Overmans and Haar comprise those actually killed in the course of the expulsion measures, while the estimates above two million also include people who died of disease, hunger, cold and Allied air raids while on their way to one or the other German zones.[105][115] Ingo Haar rejects this "mistaken interpretation" of the estimates and says that the deaths due to disease, hunger and other conditions are already included in the lower numbers.[118] According to Ingo Haar the numbers have been set too high for decades, for postwar political reasons.[115]

Rudolph Joseph Rummel says that it is impossible to calculate an accurate number of dead, because few public records were kept and the situation was complex due to mass flights and attempts of people to return in the late war period and after.[104] Rummel says one has to rely on population balances for casualty estimates.[104]

Condition of the expellees after arriving in post-war Germany

Those who arrived were in bad shape—particularly during the harsh winter of 1945-46, when arriving trains carried "the dead and dying in each carriage (other dead had been thrown from the train along the way)".[83] After experiencing Red Army atrocities, Germans in the expulsion areas were subject to harsh punitive measures by Yugoslav partisans and in post-war Poland and Czechoslavakia.[106] Beatings, rapes and murders accompanied the expulsions.[83][106] Some had experienced massacres, such as the Ústí (Aussig) massacre, in which 80-100 ethnic Germans died, or conditions like those in the Upper Silesian Camp Łambinowice (Lamsdorf), where interned Germans were exposed to sadistic practices and at least 1,000 perished.[106] In addition to the atrocities, the expellees had experienced hunger, thirst and disease, separation from family members, loss of civil rights and familiar environment,and sometimes internment and forced labour.[106] Thus, many expellees were traumatized and carried a psychological burden for years, which especially the young and elderly were often unable to cope with.[106]

Once they arrived, they found themselves in a country devastated by war. Housing shortages lasted until the 1960s, which along with other shortages led to conflicts with the local population.[102][135] The situation eased only with the West German economic boom in the 1950s that drove unemployment rates close to zero.[136]

France did not participate in the Potsdam Conference, so it felt free to approve some of the Potsdam Agreements and dismiss others. France maintained the position that it had not approved the expulsions and therefore was not responsible for accommodating and nourishing the destitute expellees in its zone of occupation. While the French military government provided for the few refugees who arrived before July 1945 in the area that became the French zone, it succeeded in preventing entrance by later arriving ethnic Germans deported from the East.[137]

Britain and the U.S. protested the actions of the French military government but had no means to force France to bear the consequences of the expulsion policy agreed upon by American, British and Soviet leaders in Potsdam. France persevered with its argument to clearly differentiate between war-related refugees and post-war expellees. In December 1946 it absorbed into its zone German refugees from Denmark,[138] where 250,000 Germans traveled by sea between February and May 1945 to take refuge from the Soviets. These were refugees from the eastern parts of Germany, not expellees; Danes of German ethnicity remained untouched and Denmark did not expel them. With this humanitarian act the French saved many lives, due to the high death toll German refugees faced in Denmark.[139]

Until the summer of 1945, the Allies had not reached an agreement on how to deal with the expellees. France suggested emigration to South America and Australia and the settlement of 'productive elements' in France, while the Soviets SMAD suggested a resettlement of millions of expellees in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern.[140]

The Soviets, who encouraged and partly carried out the expulsions, offered little cooperation with humanitarian efforts, thereby requiring the Americans and Britons to absorb the expellees in their zones of occupation. In contradiction with the Potsdam Agreements, the Soviets neglected their obligation to provide supplies for the expellees. In Potsdam, it was agreed[141] that 15% of all equipment dismantled in the Western zones—especially from the metallurgical, chemical and machine manufacturing industries—would be transferred to the Soviets in return for food, coal, potash (a basic material for fertilisers), timber, clay products, petroleum products, etc. The Western deliveries started in 1946, but this turned out to be a one-way street. The Soviet deliveries—desperately needed to provide the expellees with food, warmth, and basic necessities and to increase agricultural production in the remaining cultivation area—did not materialize. Consequently, the U.S. stopped all deliveries on 3 May 1946,[142] while the expellees from the areas under Soviet rule were deported to the West until the end of 1947.

In the British and U.S. zones the supply situation worsened considerably, especially in the British zone. Due to its location on the Baltic, the British zone already harbored a great number of refugees who had come by sea, and the already modest rations had to be further shortened by a third in March 1946. In Hamburg for instance, the average living space per capita, reduced by air raids from 13.6 square metres in 1939 to 8.3 in 1945, was further reduced to 5.4 square metres in 1949 by billeting refugees and expellees.[143] In May 1947, Hamburg trade unions organized a strike against the small rations, with protesters complaining about the rapid absorption of expellees.[144]

The U.S. and Britain had to import food into their zones, even as Britain was financially exhausted and dependent on food imports after having fought Nazi Germany for the entire war, partly as the single opponent (during the period when France was defeated, the US had not yet entered the war, and the Soviet Union had invaded Eastern Poland, the Baltic states, and Finland, as agreed with Nazi Germany in the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact). Consequently, Britain had to incur additional debt to the U.S. and the U.S. had to spend more for the survival of its zone, while the Soviets gained applause among Eastern Europeans—many of whom were impoverished by the war and German occupation—who plundered the belongings of refugees and expellees, often before they were actually expelled. Since the Soviet Union was the only power among the Allies that allowed and/or encouraged the looting and robbery in the area under its military influence, the perpetrators and profiteers blundered into a situation in which they became dependent on the perpetuation of Soviet rule in their countries in order not to be dispossessed of the booty and to stay unpunished.

With ever more expellees sweeping into post-war Germany, the Allies' moved towards a policy of assimilation, which was believed to be the best way to stabilise Germany and ensure peace in Europe by preventing the creation of a marginalised population.[140] This policy led to the granting of German citizenship to the expellees like the Volksdeutsche, who had before their expulsion held citizenship as Poles, Czechoslovaks, Hungarians, Yugoslavs, Romanians, etc.

When the Federal Republic of Germany was founded, a law was drafted on 24 August 1952 that was primarily intended to ease the financial situation of the expellees. The law, termed Lastenausgleichsgesetz, granted partial compensation and easy credit to the expellees; the loss of their civilian property had been estimated at 299.6 billion Deutschmarks (out of a total loss of German property due to the border changes and expulsions of 355.3 billion Deutschmarks).[145] Administrative organisations were set up to integrate the expellees into post-war German society. While the Stalinist regime in the Soviet occupation zone did not allow the expellees to organise, in the Western zones expellees over time established a variety of organisations.[146] The most prominent—still active today—is the Federation of Expellees (Bund der Vertriebenen).

"War children" of German ancestry in Western and Northern Europe

In countries occupied by Nazi Germany during the war whose population was not dubbed "inferior" (Untermensch) by the Nazis, fraternisation between Wehrmacht soldiers and indigenous women in some cases resulted in offspring. After the Wehrmacht's withdrawal, these women and their children of German descent were ill-treated.[147][148] Though plans were made in Norway to expel the children and their mothers to Australia, these plans were never executed. For many war children, the situation would ease only decades after the war.[149]

Reasons and justifications for the expulsions

Given the complex history of the affected regions and the divergent interests of the victorious Allied powers, it is difficult to ascribe a definitive set of motives to the expulsions. The respective paragraph of the Potsdam Agreement only states vaguely: "The Three Governments, having considered the question in all its aspects, recognize that the transfer to Germany of German populations, or elements thereof, remaining in Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, will have to be undertaken. They agree that any transfers that take place should be effected in an orderly and humane manner". The major motivations revealed are:

- A desire to create ethnically homogeneous nation-states: This is presented by several authors as a key issue that motivated the expulsions.[150][151][152][153][154][155]

- View of a German minority as potentially troublesome: From the Soviet perspective, shared by the communist administrations installed in Soviet-occupied Europe, the remaining large German populations outside post-war Germany were seen as a potentially troublesome 'fifth column' that would, furthermore, because of its social structure interfere with the envisioned Sovietisation of the respective countries.[156] The western allies also saw the threat of a potential German 'fifth column', especially in Poland after the agreed-to compensation with former German territory.[150] In general, the Western allies hoped to secure a more lasting peace by eliminating the German minorities, which they thought could be done in a humane manner.[150][157]

- Another motivation was to punish the Germans;[150][152][155][158] the Allies declared them collectively guilty of German war crimes.[157][159][160][161]

- Soviet political considerations. Stalin saw the expulsions as a means of creating antagonism between the Soviet satellite states and their neighbours. The satellite states would then need the protection of the Soviet Union.[162] The expulsions served several practical purposes as well.

A desire to create ethnically homogeneous nation-states

The creation of ethnically homogeneous nation states in Central and Eastern Europe[151] was presented as the key reason for the official decisions of the Potsdam and previous Allied conferences as well as the resulting expulsions.[152] The principle of every nation inhabiting its own nation state gave rise to a series of expulsions and resettlements of Germans, Poles, Ukrainians and others who after the war found themselves outside their supposed home states.[153] The 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey lent legitimacy to the concept. Churchill cited the operation as a success in a speech discussing the German expulsions.[163][164]

In view of the desire for ethnically homogeneous nation-states it did not make sense to draw borders through regions which were already inhabited homogeneously by Germans without any minorities.

As early as on September 9, 1944, Soviet leader Khrushchev and Polish communist Osobka-Morawski of the Polish Committee of National Liberation signed a treaty in Lublin on population exchanges of Ukrainians and Poles living on the "wrong" side of the Curzon line.[153] Many of the 2.1 million Poles expelled from the Soviet-annexed Kresy, so-called 'repatriants', were resettled to former German territories, then dubbed 'Recovered Territories'.[161] Czech Eduard Benes in his decree of May 19, 1945, termed ethnic Hungarians and Germans "unreliable for the state", clearing a way for confiscations and expulsions.[165]

View of a German minority as potentially troublesome

Distrust and enmity

One of the reasons given by Stalin for the population transfer of Germans from the former eastern territories of Germany was the claim that these areas were a stronghold of the Nazi movement.[166] However neither Stalin nor the other influential advocates of this argument required that expellees be checked for their political attitudes or their activities. Even in the few cases when this happened and expellees were proven to have been bystanders, opponents or even victims of the Nazi regime, they were rarely spared from expulsion.[167] Polish Communist propaganda used and manipulated hatred of the Nazis to intensify the expulsions.[154]

With German communities living within the pre-war borders of Poland, there was an expressed fear of disloyalty of Germans in Eastern Upper Silesia and Pomerelia, based on wartime Nazi activities.[168] Created on order of Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, a Nazi ethnic German organisation called Selbstschutz carried out executions during Intelligenzaktion alongside operational groups of German military and police, in addition to such activities as identifying Poles for execution and illegally detaining them.[169] To Poles, expulsion of Germans was seen as an effort to avoid such events in the future and as a result, Polish exile authorities proposed a population transfer of Germans as early as 1941.[169] The Czechoslovak government-in-exile worked with the Polish government-in-exile towards this end during the war.[170]

Preventing ethnic violence

The participants at the Potsdam Conference asserted that expulsions were the only way to prevent ethnic violence. As Winston Churchill expounded in the House of Commons in 1944, "Expulsion is the method which, insofar as we have been able to see, will be the most satisfactory and lasting. There will be no mixture of populations to cause endless trouble... A clean sweep will be made. I am not alarmed by the prospect of disentanglement of populations, not even of these large transferences, which are more possible in modern conditions than they have ever been before".[171] From this point of view, the policy achieved its goals: the 1945 borders are stable and ethnic conflicts are relatively marginal.

Punishment for starting the war and Nazi crimes

The expulsions were also driven by a desire for retribution, given the brutal way German occupiers treated non-German civilians in the German occupied territories during the war. Thus, the expulsions were partly motivated by the animus engendered by the war crimes, atrocities, brutalities and uncivilised rule of the German conquerors.[152][158] Czechoslovakian President Eduard Benes, in the National Congress, justified the expulsions on 28 October 1945 by stating that the majority of Germans had acted in full support of Hitler; during a ceremony in remembrance of the Lidice massacre, he blamed all Germans as responsible for the actions of the German state.[159] In Poland and Czechoslovakia, newspapers,[172] leaflets[172] and politicians across the political spectrum,[172][173] which narrowed during the post-war Communist take-over,[173] asked for retribution for wartime German activities.[172][173] Responsibility of the German population for the crimes committed in its name was also asserted by commanders of the late and post-war Polish military.[172] Karol Świerczewski, commander of the 2nd Polish army, briefed his soldiers to "exact on the Germans what they enacted on us, so they will flee on their own and thank God they saved their lives".[172] In Poland, which had suffered the loss of six million citizens, including her elite and almost an entire Jewish population due to the Holocaust and the lebensraum concept, most Germans were seen as Nazi-perpetrators who could now finally be collectively punished for their past deeds.[161]

The Allies' Nuremberg Trials dealt only with individuals. The Trials indicted and found guilty numerous top Nazis for crimes against humanity and a variety of war crimes.

Soviet political considerations

Stalin, who had earlier directed a number of population transfers in the Soviet Union, strongly supported the expulsions, which worked to the Soviet Union's advantage in several ways. The satellite states would now feel the need to be protected by the Soviets from German anger over the expulsions.[162] The assets left by the expellees in Poland and Czechoslovakia were successfully used to reward cooperation with the new governments, and support for the Communists was especially strong in areas that had seen significant expulsions. Settlers in these territories welcomed the opportunities presented by their fertile soils and vacated homes and enterprises, increasing their loyalty.[174]

Legacy of the expulsions

With at least[105] 12 million[33][175][176] Germans directly involved, possibly 14 million[102][103] or more,[104] it was the largest movement or transfer of any single ethnic population in modern history[176][177][178] and largest among the post-war expulsions in Central and Eastern Europe (which displaced more than twenty million people in total).[175]

The exact number of Germans expelled after the war is still unknown, because most recent research provides a combined estimate which includes those who were evacuated by the German authorities, fled or were killed during the war. However, it is estimated that between 12 and 14 million ethnic Germans and their descendants were displaced from their homes. The exact number of casualties is still unknown and is difficult to establish due to the chaotic nature of the last months of the war.

Census figures placed the total number of ethnic Germans still living in Eastern Europe in 1950, after the major expulsions were complete, at approximately 2.6 million, about 12 percent of the pre-war total.[50]

The events have been usually classified as population transfer,[179] or as ethnic cleansing.[180] R. J. Rummel has classified these events as democide,[104] and a few go as far as calling it a genocide.[181]

The expulsions created major social disruptions in the receiving territories, which were tasked with providing housing and employment for millions of refugees.[182] West Germany established a ministry dedicated to the problem, and several laws created a legal framework. The expellees established several organisations, some demanding compensation. Their grievances, while remaining controversial, were incorporated into public discourse.[182] During 1945 the British press aired concerns over the refugees' situation;[183] this was followed by limited discussion of the issue during the Cold War outside West Germany.[184] East Germany sought to avoid alienating the Soviet Union and its neighbours; the Polish and Czechoslovakian governments characterised the expulsions as "a just punishment for Nazi crimes".[182] Western analysts were inclined to see the Soviet Union and its satellites as a single entity, disregarding the national disputes that had preceded the Cold War.[185] The fall of the Soviet Union and the unification of Germany opened the door to a renewed examination of the expulsions in both scholarly and political circles.[186] A factor in the ongoing nature of the dispute is the high proportion of the German citizenry that consists of expellees and their descendents, estimated at about 20% in 2000.[187]

Status in international law

International law on population transfer underwent considerable evolution during the 20th century. Before World War II, a number of major population transfers were the result of bilateral treaties and had the support of international bodies such as the League of Nations. The tide started to turn when the charter of the Nuremberg Trials of German Nazi leaders declared forced deportation of civilian populations to be both a war crime and a crime against humanity, and this opinion was progressively adopted and extended through the remainder of the century. Underlying the change was the trend to assign rights to individuals, thereby limiting the rights of nation-states to impose fiats which adversely affected them. The Charter of the then newly formed United Nations stated that its Security Council could take no enforcement actions regarding measures taken against World War II "enemy states", defined as enemies of a Charter signatory in World War II.[188] The Charter also stated that it did not preclude action in relation to such enemies "taken or authorized as a result of that war by the Governments having responsibility for such action."[188] Thus, the Charter did not invalidate or preclude action against World War II enemies following the war.[188] This argument is, however, contested by American professor of international law Alfred de Zayas.[189] ICRC's legal adviser Jean-Marie Henckaerts says that the contemporary expulsions conducted by the Allies of World War II themselves were the reason why expulsion issues were included neither in the UN Declaration of Human Rights of 1948, nor in the European Convention on Human Rights in 1950, and says it "may be called 'a tragic anomaly'" that while deportations were outlawed at Nuremberg they were used by the same powers as a "peacetime measure".[190] It was only in 1955 that the Settlement Convention regulated expulsions, yet only in respect to expulsions of individuals of the states who signed the convention.[190] The first international treaty condemning mass expulsions was a document issued by the Council of Europe on 16 September 1963 titled Protocol No 4 to the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms Securing Certain Rights and Freedoms Other than Those Already Included in the Convention and in the First Protocol [sic!],[190] stating in Article 4: "collective expulsion of aliens is prohibited".[191] This protocol entered into force on 2 May 1968, and as of 1995 was ratified by 19 states.[191]

There is now little debate about the general legal status of involuntary population transfers: "Where population transfers used to be accepted as a means to settle ethnic conflict, today, forced population transfers are considered violations of international law."[192] No legal distinction is made between one-way and two-way transfers, since the rights of each individual are regarded as independent of the experience of others.

Although the signatories to the Potsdam Agreements and the expelling countries may have considered the expulsions to be legal under international law at the time, there are historians and scholars in international law and human rights who argue that the expulsions of Germans from Central and Eastern Europe should now be considered as episodes of ethnic cleansing, and thus a violation of human rights. For example, Timothy V. Waters argues in "On the Legal Construction of Ethnic Cleansing" that if similar circumstances arise in the future, the precedent of the expulsions of the Germans without legal redress would also allow the future ethnic cleansing of other populations under international law.[193] In the 1970s and 1980s a Harvard-trained lawyer and historian, Alfred de Zayas, published Nemesis at Potsdam and A Terrible Revenge, both of which became bestsellers in Germany.[194] De Zayas argues that the expulsions were war crimes and crimes against humanity even in the context of international law of the time, stating "the only applicable principles were the Hague Conventions, in particular, the Hague Regulations, ARTICLES 42-56, which limited the rights of occupying powers – and obviously occupying powers have no rights to expel the populations – so there was the clear violation of the Hague Regulations".[194][195][196] He also argued that they violated the Nuremberg Principles.[194] In November 2000 a major conference on ethnic cleansing in the 20th century was held at Duquesne University, along with the publication of a book containing participants' conclusions.[197]

Numerous human rights experts have argued that all victims deserve compassion, and that it is unacceptable to discriminate amongst victims or to apply principles of collective guilt to innocent civilian populations. The first UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, José Ayala Lasso (Ecuador) endorsed the establishment of the Centre Against Expulsions in Berlin.[198] Ayala Lasso gave the German expellees recognition as victims of gross violations of human rights.[199] Professor de Zayas, a member of the advisory board of the Stiftung Zentrum gegen Vertreibungen, endorses the full participation of the organisation representing the expellees, the Bund der Vertriebenen, in the Centre in Berlin.[200]

Political issues

In 1990 the Czechoslovakian President Vaclav Havel requested forgiveness on his country's behalf, notably using the term expulsion rather than transfer.[201][202] Public approval for Havel's stance was limited; in a 1996 opinion poll, 86% of Czechs stated they would not support a party that endorsed such an apology.[203] The expulsion topic also surfaced in 2002 during the Czech Republic's application for membership in the European Union, since the authorisation decrees issued by Edvard Benes had not been formally renounced.[204]

A Centre against Expulsions is to be set up in Berlin by the German government based on an initiative and with active participation of the German Federation of Expellees. The Centre's creation has been criticized in Poland.[205] It was strongly opposed by the Polish government and president Lech Kaczyński. Current Polish prime minister Donald Tusk restricted his comments to a recommendation that Germany pursue a neutral approach at the museum.[205] According to the Polish position, the centre seeks to paint a population of Germans as victims of World War II. Many in Poland argue that there is no moral equivalent to how Jews, Poles, Russians, Romani people and many others suffered at the hands of the German Nazis.[206]

In October 2009 the Czech President Vaclav Klaus stated that the Czech Republic would require exemption from the European Charter of Fundamental Rights in order to ensure that the descendents of expelled Germans were unable to press claims against the Republic.[207]

See also

- A Terrible Revenge, a book by Alfred-Maurice de Zayas

- Bakker-Schut Plan

- Ethnic cleansing

- Expulsion of Poles by Germany

- Federation of Expellees

- German exodus from Eastern Europe

- Nazi crimes against ethnic Poles

- Operation Paperclip

- Organised persecution of ethnic Germans

- Population transfer

- Population transfer in the Soviet Union

- Pursuit of Nazi collaborators

- Treaty of Zgorzelec

- Victor Gollancz

- World War II crimes in Poland

- World War II-era population transfers

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Kati Tonkin reviewing Jurgen Tampke, Czech-German Relations and the Politics of Central Europe: From Bohemia to the EU The Australian Journal of Politics and History, March, 2004 Findarticles.com

- ↑ A History of Modern Germany: 1840-1945. Hajo Holborn, Princeton University Press, 1982 page 449

- ↑ Lumans, Valdis O., Himmler's Auxiliaries: The Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle and the German National Minorities of Europe, 1939-1945, The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 1993, pp. 243, 257-260.

- ↑ Kashima, Tetsuden (2003). Judgment without trial: Japanese American imprisonment during World War II. University of Washington Press. p. 124. ISBN 0295982993.

- ↑ Adam, Thomas, ed (2005). Transatlantic relations series. Germany and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History : a Multidisciplinary Encyclopedia. Volume II. ABC-CLIO. pp. 181–182. ISBN 1851096280.

- ↑ Kashima, Tetsuden, ed (1997). Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Part 769: Personal justice denied. University of Washington Press. pp. 287–288. ISBN 029597558X.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Gibney, Matthew J; Hansen, Randall (2005). Immigration and Asylum: From 1900 to the Present. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. p. 197. ISBN 1576077969.

- ↑ "Agreements of the Berlin (Potsdam) Conference, July 17-August 2, 1945". PBS. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/truman/psources/ps_potsdam.html. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- ↑ *Hoffmeister, Gerhart; Reinhardt, Kurt Frank; Tubach, Frederic C (1992). Tubach, Frederic C. ed. Germany: 2000 Years : Volume III : From the Nazi Era to German Unification (2 ed.). Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 57. ISBN 0826406017. http://www.google.de/books?id=glMpTyiRXDoC&pg=PA57. Retrieved 28 August 2009.